Act to Action: US Quantum Computing Policy Past, Present, and Future

From one POTUS to another, quantum policy marches on. Plus, I did a podcast!

Welcome! This is The Quantum Stack. Created by a Travis L. Scholten, it brings clarity to the topic of quantum computing, with an aim to separate hype from reality and help readers stay on top of trends and opportunities. To subscribe, click the button below.

Update 2024/12/10: For a deeper dive into the paper referenced in the podcast (Assessing the Benefits and Risks of Quantum Computers), see this article.

Just a few days after the US election, I was featured on The Dynamist, a podcast produced by the Foundation for American Innovation. In From Quantum Realm to Quantum Reality, I discussed the current state of quantum computing and its implications for governments as they seek to promote the economic benefits of this technology while managing its cybersecurity risks. Available on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

Given this, an article about the backdrop of quantum technology policy in the US seemed in order. It’s timely as well because shortly after I joined IBM Quantum approximately six years ago was when the US government (USG) launched its signature policy initiative in quantum, the National Quantum Initiative (NQI) Act. Since the NQI Act, additional policy activities have taken place in both the Executive and Legislative branches. In this article, I’ll review the NQI Act, subsequent policy activities, and the prospect of an NQI Act 2.0.

Note: this article is a bit heavy on policy jargon and acronyms!

By way of a brief summary: the NQI Act of 2018 and the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 have accelerated the US’ capabilities in quantum. They have laid solid organizational infrastructure for future QIS growth in the Nation. However, gaps definitely remain, particularly around creating a market pull for quantum and driving the adoption of quantum as a tool for computational science. Because the NQI Act was authorized only for 5 years, it is currently under consideration for reauthorization by Congress. An ambitious NQI Act 2.0 which not only supports exciting near-term research progress, but also drives the development of genuinely useful quantum applications, as well as lays the groundwork for the tough science necessary to create the quantum computers of 20 years from now, would be a great piece of legislation.

The National Quantum Initiative (NQI) Act

The National Quantum Initiative (NQI) Act was signed into law by President Trump in December 2018. This bill, which directs the President to develop and implement a 10-year plan to accelerate QIS in the US, authorized USG to spend up to ~$1.2B USD over the first 5 years to support those activities. Some key provisions of the bill included:

Establishing the National Quantum Coordination Office (NQCO) within the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to, as the name implies, coordinate QIS efforts across USG. The creation of the NQCO led to the development of a very unique logo for the office!

Having the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) launch a public-private consortium. This led to the creation of the Quantum Economic Development Consortium (QED-C).

Directing the Department of Energy (DOE) to establish up to 5 National Quantum Information Science Research Centers. These 5 Centers, spanning the DOE research complex, have produced a large amount of work on QIS. The Centers have a joint website promoting their activities here.

Directing the National Science Foundation (NSF) to establish up to 5 Multidisciplinary Centers for Quantum Research and Education. These Centers, dubbed the “Quantum Leap Challenge Institutes”, have ended up focusing on topics as diverse as building quantum computers, developing new quantum algorithms, and exploring/applying quantum sensing.

While the NQI Act specifically focused on NIST, NSF, and DOE, legislation was also put into law regarding how the Department of Defense (DOD) should engage with QIS. Based on the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) – widely considered a piece of “must-pass” legislation each year – for fiscal year 2020, DOD designated 4 defense-related QIS R&D centers. These centers are: the National Security Agency’s Laboratory for Physical Sciences (LPS) Qubit Collaboratory (LQC), Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL), Naval Research Laboratory (NRL), and the Army Research Laboratory (ARL).

More information and reports on the NQI Act and USG’s implementation thereof can be found at the NQCO’s website.

Policy Since the NQI Act

Building upon the foundation of the NQI Act, subsequent policies during President Biden’s Administration have further shaped the US quantum landscape.

Legislative Policies

One of the signature policy initiatives of that Administration, the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, has had a significant effect on QIS in the US. A few of the quantum-relevant provisions in the “CHIPS Act” included:

Directing DOE to include QIS as a topic in its Computational Science Graduate Fellowship program, and NSF to include the topic in its Federal Cyber Scholarship-for-Service Program.

Establishing the Technology, Innovation, and Partnerships (TIP) Directorate within the NSF. TIP has gone on to create the NSF Engines program, which supports the creation of place-based, regional innovation ecosystems. NSF Engines awards are $15 million over 2 years, and then up to $160 million over the next decade. Although no QIS-relevant awards were made during the first round of awards, 4 QIS-centric proposals have been invited to move forward during a new, second round. These proposals, coming from NM, SC, CT, and IL, seek to leverage QIS as a way to turbocharge regional innovation.

Creating the “Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs” (TechHubs) program within the Economic Development Agency (a bureau within the Department of Commerce). One of the designated TechHubs, spanning CO and NM, will be receiving $41M to support QIS-relevant activities.

Establishing a “Microelectronics Commons” program within the Department of Defense (DOD). Of the 8 initial hubs created under the program, 4 include quantum technologies as a supported topic.

Sundry other provision for NIST, NSF, and DOE. Details here.

The “place-based development” programs (NSF Engines, EDA TechHubs, and the DOD Microelectronics Commons program) are significant because they seek to foster regional technology ecosystems. Over the next several years, it is likely a handful of regions will emerge as clear leaders in the US QIS ecosystem.

Executive Policies

In addition to policies enacted through the Legislature, several Executive actions have been undertaken as well. These actions have sought to enhance the US’ cybersecurity posture, protect American intellectual property, and ensure US investors do not inadvertently support QIS activities at un-allied nations. Executive actions have included:

Promulgating National Security Memorandum 10 (NSM-10) in 2022 May, which among other things: (a) encourages USG to get quantum safe by 2035, (b) directs the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) via its Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) to accelerate the adoption of quantum safe technologies for critical infrastructure providers, and (3) requires the heads of all Federal Civilian Executive Branch Agencies to report annually on their progress in getting quantum safe. It’s worth noting that the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) put out a report in 2024 July estimating that transitioning federal agencies to quantum safe cryptography will cost approximately $7.1B.

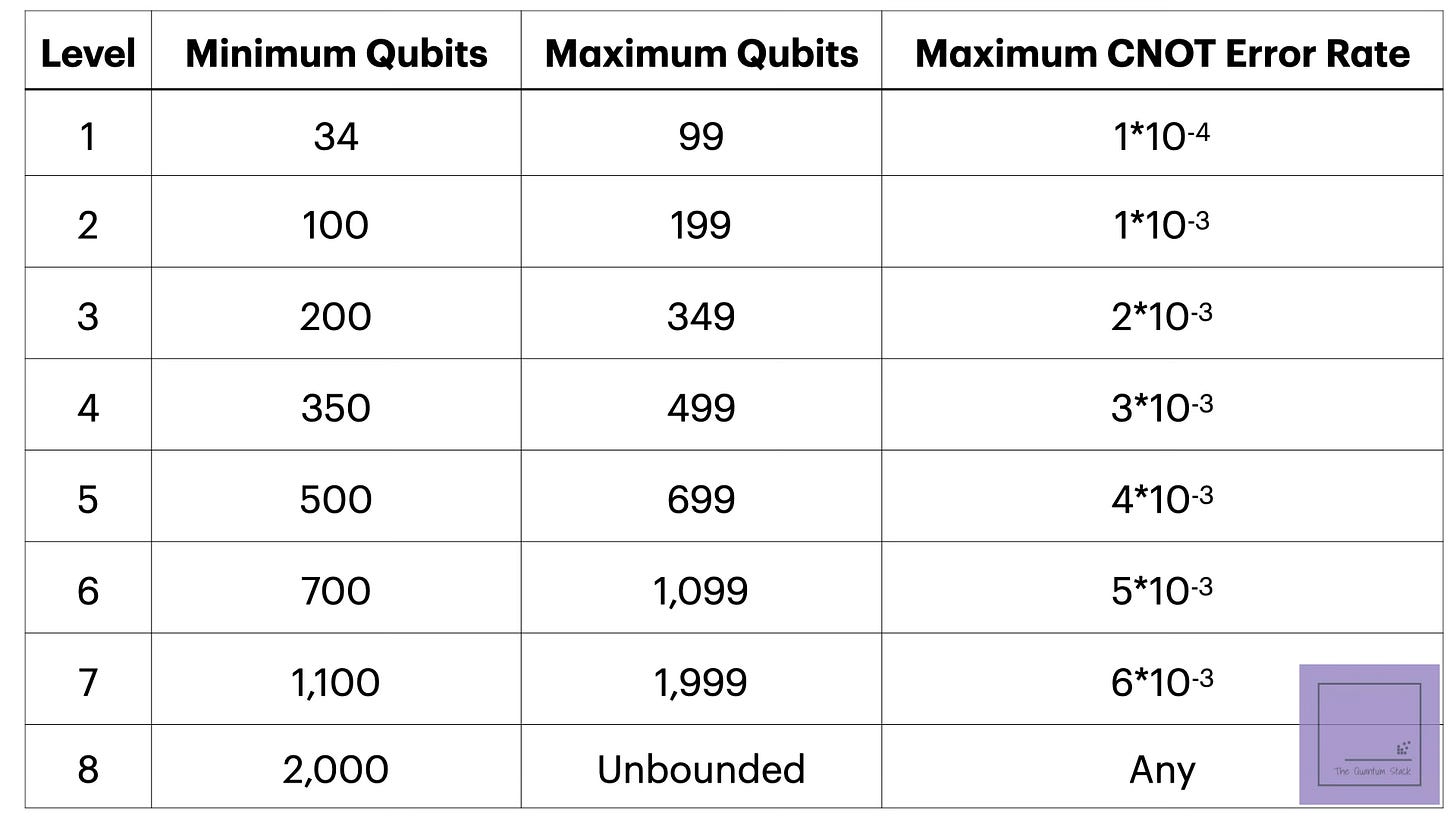

The Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS), part of the Department of Commerce, enacted export controls on quantum computers in 2024 September. These controls require US companies to obtain licenses when deploying certain quantum computers abroad. In addition, the controls establish a framework by which exports can take place to countries which have enacted “similar-enough” controls themselves. Interestingly, the criteria used in the controls relate to qubit count and 2-qubit error rates. I did a thread on X about these controls; see here.

The US Treasury has recently (2024 October) established a program regarding outbound investments (i.e., investments made by US entities into companies and entities abroad). As part of this program, the Treasury Department issued a rule regarding obligations to inform the Treasury Department about certain outbound investments. This rule includes quantum, and requires notification if the outbound investment would support the development of quantum computers (or critical components), quantum sensing platforms, and certain kinds of quantum networks and communication systems.

NQI Act 2.0 and the future of QIS in the US

When President Trump signed the NQI Act in 2018, the authorities it granted the US government ran for 5 years. As such, the NQI Act’s authorizations expired last year, and have not (yet!) been renewed. The 118th Congress does have a bill before it to reauthorize the NQI Act (H.R. 6123, the National Quantum Initiative Reauthorization Act) which was introduced 1 year ago. Some interesting provisions in the Act include:

Requiring the OSTP to develop a strategy for cooperative research efforts with US allies.

Authorizing NIST to establish its own centers (up to 3).

Authorizes NASA to establish a quantum institute. It should be noted NASA has a pre-existing quantum computing research team at its Quantum Artificial Intelligence Lab (QuAIL). So this language seems to be more about putting that activity on a firmer footing, legislatively, and also raising NASA’s prominence in terms of US agencies looking at quantum.

Authorizes the NSF to create a new coordination hub supporting workforce development and developing pathways to jobs in the quantum industry.

Directs the Secretary of Energy to develop a strategy for promoting the commercialization of quantum computing.

Authorizes DOE to create quantum foundries which can support device/material needs in the relevant supply chains.

Other Quantum Policy Provisions

In addition there have been other standalone bills introduced building on the work of NQI 1.0, including:

The DOE Quantum Leadership Act (S. 4392) focuses specifically on DOE. It would authorize DOE to work on QIS through 2029, and authorize up to $2.5B in funding to do so.

The Defense Quantum Acceleration Act (H.R. 7935 & S.4105) focuses specifically on DOD. It would create the position of “Principal Quantum Advisor to the Secretary of Defense”, requiring that person to develop a strategic quantum roadmap for the DOD, among other things.

S.2450, A bill to improve coordination between the Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation on activities carried out under the National Quantum Initiative Program, and for other purposes, seeks to ensure DOE and NSF work harmoniously in implementing the NQI, and also establish a Manufacturing USA Institute for Quantum Manufacturing.

The Quantum Sandbox for Near-Term Applications Act of 2023 (H.R. 2739 & S. 1439) directs the Department of Commerce and NIST to establish a public-private partnership whose purpose is to accelerate the development of near-term quantum applications.

The Leveraging Quantum Computing Act (H.R. 3987) directs the NQCO to engage with federal agencies to identify agency-relevant use cases, and create a plan for developing them.

Overall, these bills would do a good job of helping advance US leadership in QIS. While we currently are in a lame-duck session of Congress, perhaps one or several of these could advance forward for President Biden’s signature. Given the popularity and broad support of QIS across both political parties, I would hope this happens.

Some Policy Recommendations

Towards the end of my time on the podcast, I offered a few thoughts on what kind of policy changes I would like to see take place. In case you don’t listen to the podcast, here’s what I shared. The core idea is that the US government can help facilitate a “demand pull” for quantum computing capabilities, thereby more firmly establishing a market for this technology.

Increase the ease with which researchers can include the cost of access to quantum computers in their grant proposals. QCs are rather expensive things, and right now the expectations of program managers do not seem to be well-calibrated for how much access and cost are necessary to support cutting-edge research. As such, researchers applying for grants often are put in a situation where they can get money for their students and postdocs, but no access, or they can get access, but can’t support their students. Ideally, program managers internalize that they should expect to see larger dollar requests in proposals, and support them.

Establish a national quantum computing facility. This idea is complementary to the previous one – instead of researchers putting the cost of access into a proposal, why not simply establish an access facility and distribute time to the research community? The US has a history of operating advanced computing capabilities for researchers – the DOE, in particular, but also the NSF – and that institutional know-how could be deployed for quantum. Given a similar idea has cropped up in AI – with the NSF establishing the National AI Research Resource (NAIRR) – establishing a facility for quantum doesn’t seem so far-fetched.

Wrap Up: the Global Quantum Race

Over the past 6 years a flurry of activity has happened here in the US (and abroad). The NQI Act 1.0 triggered a good amount of engagement across the US government with quantum, and a solid foundation has been built. But quantum computing is a marathon, not a sprint.

In parallel, the need for the country’s cybersecurity to be made quantum safe needs to keep being emphasized. The transition to quantum safe cryptography will take a while, and 2035 – the nominal deadline for the US government to make the transition – isn’t that far away all things considered.

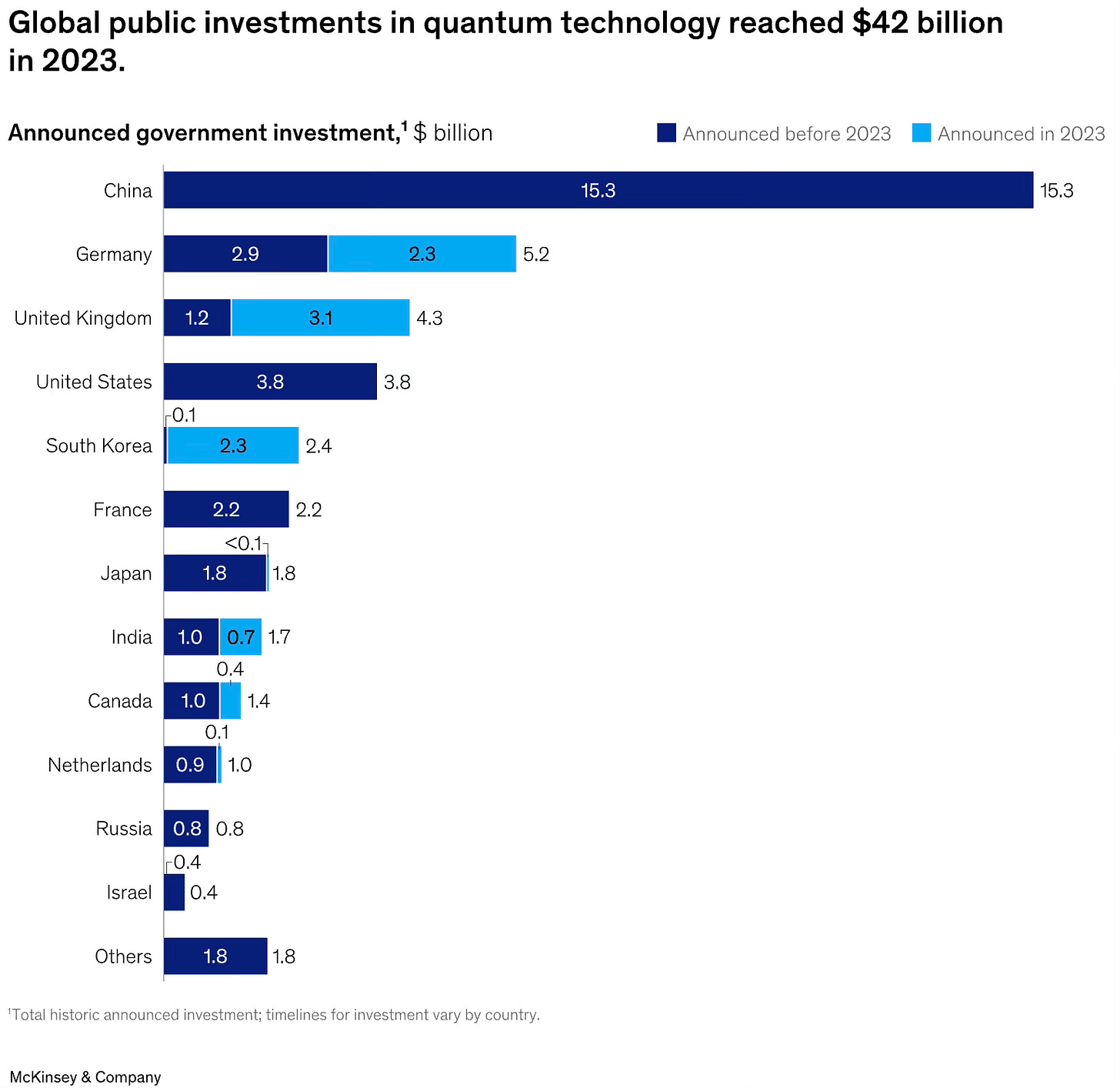

Thankfully, quantum is a topic which both fascinates and delights, and is likely to continue enjoying bipartisan support for the foreseeable future. This is good, because the global context has significantly shifted since 2018. New countries are launching their own quantum initiatives and the geopolitical tussle for influence and leadership continues; see the above image indicating the announced public spending in quantum technologies.

The US has inked 11 bilateral agreements around quantum, and the 2021 Australia-UK-US (AUKUS) agreement includes it as a component. These highlight the geopolitical significance of this technology. The focus of this article being domestic policy, I won’t go into more details here. But I will observe that technology is increasingly being seen as a tool for diplomacy and geopolitical influence. Given the security implications of quantum computing, the use of this particular technology as a tool for those ends is likely to continue.

While the nascent quantum computing industry has laid out bold plans over the next 5-10 years, the need still exists for government support. An ambitious NQI Act 2.0 which not only supports exciting near-term research progress, but also drives the development of genuinely useful quantum applications, as well as lays the groundwork for the tough science necessary to create the quantum computers of 20 years from now, would be a great piece of legislation.

P.S. In addition to The Quantum Stack, you can find me online here.

Was this article useful? Please share it.

Note: All opinions expressed in this post are my own, are not representative or indicative of those of my employer, and in no way are intended to indicate prospective business approaches, strategies, and/or opportunities.

Copyright 2024 Travis L. Scholten